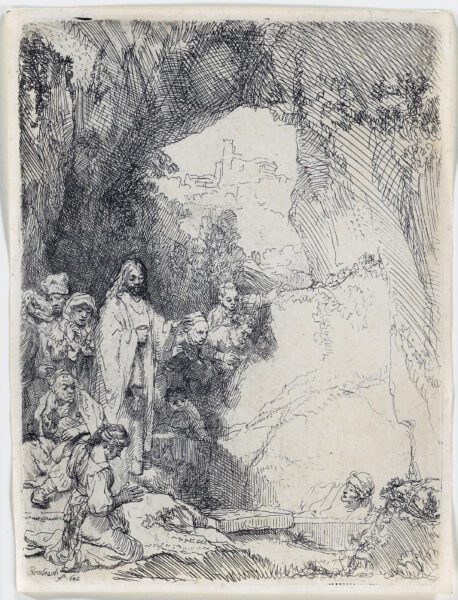

“The Raising of Lazarus: small plate”, 1642

signed and dated lower left: Rembrandt f 1642

etching with touches of drypoint on laid paper: 15,6 x 11,8 cm

with an Arms of Amsterdam watermark

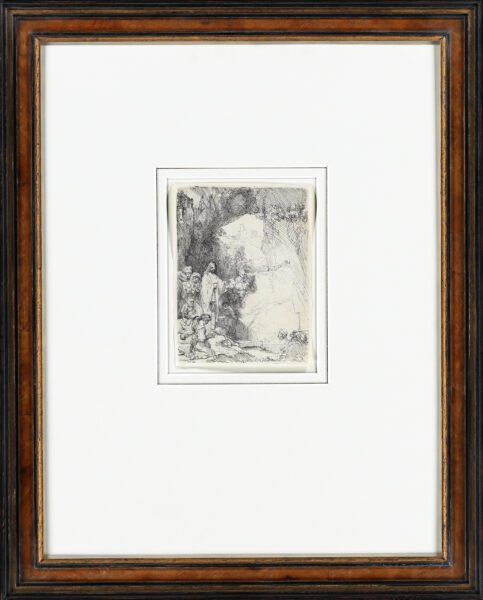

with good margins on all four sides.

"*" indicates required fields

Notes

During his lifetime, Rembrandt’s extraordinary skills as a printmaker were the main source of his international fame. Unlike his oil paintings, prints travelled light and were relatively cheap. For this reason, they soon became very popular with collectors not only within, but also beyond the borders of the Netherlands.

The Raising of Lazarus is a subject that repeatedly inspired Rembrandt, seen in his early oil painting (c. 1630-32; Los Angeles Country Museum of Art: see next page) as well as in two etchings, the more intricate and realist ‘Large Plate’ of 1632 and this more economical ‘Small Plate’ of ten years later. It depicts Christ standing with others to the left of the cave/tomb where Lazarus was raised from death, and his figure miraculously emerging. Perhaps less idealistically than the earlier work, it shows Christ as more of a healer than an enchanter. Indeed, art writer Sister Wendy Beckett claims that Jesus is portrayed here as a weary magician rather than a triumphant saviour.

In the evangelist John’s account of Jesus’ miraculous raising of his friend Lazarus from the dead (John 11:1-44), Christ explains to Lazarus’s sister, Martha, the broader significance of the miracle before he performs it: through belief in him, the son of God, one shall achieve salvation and eternal life. He says, “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live,” and, “whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.” John tells us that Jesus loved Mary, Martha, and their brother Lazarus, followers of Christ residing in Bethany near Jerusalem, and that he wept for Lazarus. Christ’s resurrection of Lazarus from the dead was one of his most dramatic miracles and we are told that many witnesses to the event were converted to belief in him. It was also one of Jesus’ public acts that most seriously alarmed the reigning religious authorities and led to Christ’s subsequent arrest, trial and crucifixion.

This impression is from the first of two states, made by Rembrandt himself and before the addition (possibly by Claude-Henri Watelet) of small diagonal lines of drypoint on Lazarus’s forehead.

Literature

Bartsch 72; Hind 198;

The New Hollstein, 2013, no. 206, first state of II;

Plate in existence, currently in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

with Nowell-Usticke (1967): C2

Provenance

- private collection, United Kingdom

- Sotheby’s London

- Private collection, The Netherlands