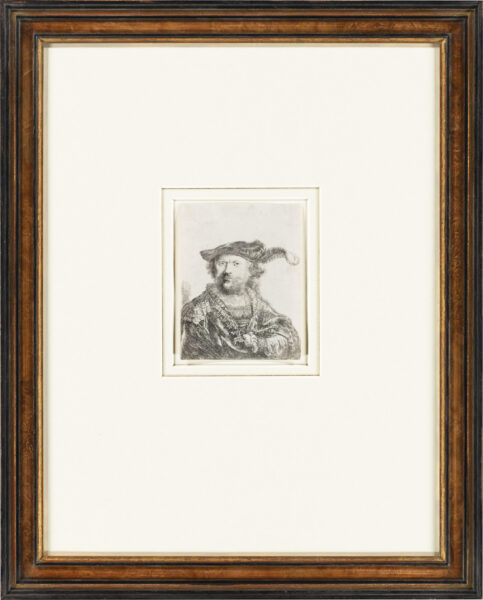

“Self-Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume”, 1638

Etching: 13,4 x 10,4 cm

signed and dated upper left (lightly visible): ‘Rembrandt. f. 1638’

"*" indicates required fields

Notes

During his lifetime, Rembrandt’s extraordinary skills as a printmaker were the main source of his international fame. Unlike his oil paintings, prints travelled light and were relatively cheap. For this reason, they soon became very popular with collectors not only within but also beyond the borders of the Netherlands, and it also explains why they were affordable to collectors through the centuries, including Bishop Ditlev Monrad, who presented this print to the Colonial Museum in 1869, and Sir John Ilott.

Rembrandt’s etchings are remarkable for their high number of self-portraits (over 30 out of about 290). These are particularly collectible, perhaps due to the smaller number of states as well as the artist’s compelling and powerful presence. Unlike his stately religious scenes, or regal, posed portraits of others, which exhibit his careful and calculating brilliance as an etcher, Rembrandt’s self-portraits reveal him as an artist and a man. In them he assumes the role of the experimenting artist, approaching the most difficult of subjects – himself. These self-portraits are often described as ethereal and wistful for their notable contrasting areas of high and low etched space.

Rembrandt’s self-portraits always tell us how he feels about himself. In 1638 he feels prosperous: his shirt and jacket are expensive and stylish; the plain artist’s beret has been supplanted by a crushed velvet hat with a plume; he has grown whiskers – all befitting a man with a long list of clients, a costly household and admiring students. Rembrandt also feels cocky: his bearing is aristocratic; his face and eyes convey a certain smugness; his hand is thrust jauntily into the folds of his garment. The scale and ostentation of this self-portrait contrast sharply with the modest, intimate studies of 1630-1631, which reveal only his head and shoulders.

Another reading is possible: his costume is anachronistic, really fancy dress – is he looking back to past artists, such as Titian and Gossaert? Or even grander figures, like their aristocratic sitters themselves? And while he looks haughty, others have regarded this look as conveying ‘an electric creative energy’. Both interpretations could be right. What we do know, is that this ‘regal’ phase of Rembrandt’s career was not to last, and within a decade he was no longer flavour of the month among the Amsterdam bourgeoisie. His portraits, self or otherwise, are no longer so uncompromisingly proud, and Rembrandt’s humanity, which art audiences in recent centuries have adored, kicked in.

Provenance

- Collection H.G. Hammar, Köln, 1917

- Private collection, Sweden

- Private collection, The Netherlands

Literature

Bartsch 20; White/Boon 20;

The New Hollstein Dutch 170 Second state (of IV) ;

Nowell-Usticke C1: Plate in existence in private collection, USA.