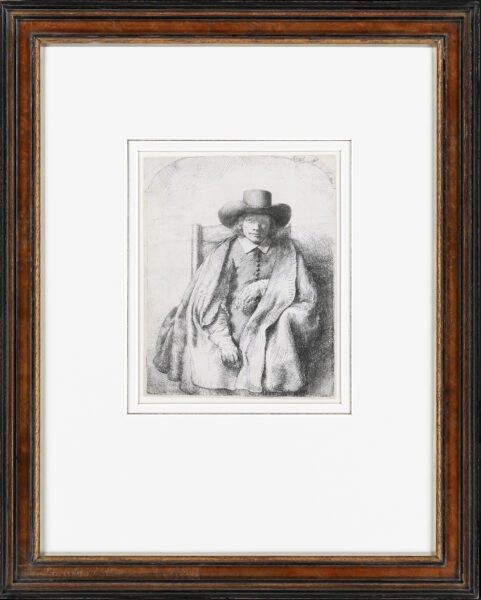

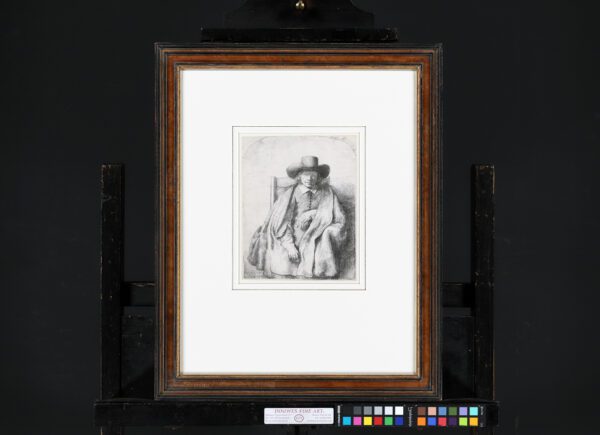

“Clement de Jonghe, Printseller”, 1651

counterproof (of the etching with drypoint and engraving): 20,8 x 16,6 cm;

Signed and dated lower left in reverse: Rembrandt f 1651

with small margins on three sides

"*" indicates required fields

Notes

During his lifetime, Rembrandt’s extraordinary skills as a printmaker were the main source of his international fame. Unlike his oil paintings, prints travelled light and were relatively cheap. For this reason, they soon became very popular with collectors not only within, but also beyond the borders of the Netherlands.

The first five states of this portrait are by Rembrandt’s own hand, all subsequent states are the result of posthumous changes to the plate. Of these five lifetime states, only six counterproofs are recorded in New Hollstein: one of the first state; three of the second state; two of the third state; and none of the present fourth or the fifth state. The present example thus constitutes an important and rare addition to the census of early impressions of this print, and of counterproofs in Rembrandt’s oeuvre in general.

A Rembrandt etching counterproof is a unique type of print made by transferring an image from a freshly printed sheet to another. Being printed from another print and not directly from the plate, counterproofs are reversed, resulting in the image being shown in the same direction as it is on the plate. This allowed the artist to see whether and how certain changes should be made on the plate. In some instances, Rembrandt used this method to try out certain revisions or additions to an image by drawing onto a counterproof. Occasionally however, he must have printed counterproofs simply because there was a market for such rare variants or oddities. It allowed him to sell the same print twice to the same collector: once as a print, once as a counterproof.

In this remarkable portrait, Rembrandt combined a very bold composition with an astonishingly subtle depiction of the sitter’s face and his wry expression, which gets lost in later impressions but is very lively and moving in the present, brilliant impression of the rare first state.

By the 1650’s Rembrandt had abandoned the elaborate technical devices of his earlier portraits in favour of a simpler, more monumental style. Unusually, the subject is presented frontally, rather than the favoured three-quarters view, enveloped in a cloak defined in a few broad, heavy folds. The pose is informal, giving the impression that the sitter has just dropped by the studio momentarily. A high-backed chair lends stability and balance to the composition, but Rembrandt ensures that the overall effect is relaxed by having the sitter lean to the left, rather than depicting him dead-centre.

A prominent Amsterdam print dealer with a shop on the Kalverstraat, Clement de Jonghe (1624/5-1677) does not appear to have had extensive business relations with Rembrandt until, presumably during Rembrandt’s lifetime, he acquired a large of number of his copperplates and continued to print them. It is possible that the two men struck a deal during the artist’s bankruptcy period, to avoid the plates being sold publicly and thereby dispersed. The inventory of de Jonghe’s possessions, written by his son Jacobus, lists 74 etched plates by Rembrandt and constitutes the first list of a significant part of Rembrandt’s graphic oeuvre. Many of the customary titles of his prints were first recorded in this document. Curiously, it did not include the present plate. Partly for this reason, partly because the man depicted may look a bit older than the 26 or 27 years of age that Clement de Jonghe would have had at the time, some scholars have expressed doubts that he is in fact the sitter (see: White, 1999, p. 153).

However, a third-state impression at the Morgan Library, New York, is inscribed by the Paris print dealer Pierre Mariette ‘Clement de Jonhge [sic] marchand de tailles douces a Amsterdam 1668’. As Nick Stogdon pointed out, Mariette did not usually annotate his prints with their provenance, only with the date of acquisition, in this case 1670. Rather than stating where or from whom he bought the print, Mariette seems to identify the sitter – and well within de Jonghe’s lifetime. Stogdon further speculated that Jacobus de Jonghe may have deliberately left this plate off the inventory, as he considered the copperplate of his father’s portrait a personal inheritance rather than just another item amongst other commercial effects (see: Stogdon, 2011, no. 113, p. 196-197).

Literature

Bartsch 272; Hind 251;

The New Hollstein, 2013, no. 264: first state (of II)

Plate in existence, Amsterdam Museum (inv. KA19319)

with Nowell-Usticke (1967): C2+

Provenance

- Private collection, United Kingdom

- Christie’s London

- Private Collection, The Netherlands